El Colonel smiles. Bright birds sing in the morning air. Limpid light through the wide

open windows bathes the high celinged room’s whitewashed stone walls. The coolness of

night, refreshing as nearby mountain streams, rises in the wake of dawn’s departing

mists. “The promise of a good day is given unto him,” El Colonel hums, imitating the

cadences of a childhood hymn.

El Colonel smiles. With practiced precision, his favorite adjutant appears, “true to the

appointed minute, ever mindful of detail.”

El Colonel smiles. Along with his great fondness for alliteration, El Colonel has an

addiction for placing thoughts, those improvised compositions, in quotation marks. This

brings “a deft touch of intriguing and entertaining irony to the most prosaic of ideas,

events, and persons “ Habituated to an imaginative isolation, El Colonel’s intellectual

companions are his “compositions” with their attendant “commentaries,” “asides,”

“digressions,” and “annotations.” By means of this “ironic distancing” he continually

invents “a hitherto unknown and as yet unpublished form of writing, never before seen

nor heard.”

El Colonel smiles. This writing is a method of creating for himself a reader who is in turn

accompanied by his own doubling as a writer. Where there had been “no one with who to

share his most intimate thoughts, the fullness and agility of his life,” there is now not only

such a companion; there is also a recorder of “his deeds and exploits.” In such a way El

Colonel simultaneously acts, writes and reads both for himself and to another, who is also

both a reader and an other author in turn, providing El Colonel with his own role as a

reader. By these means his life takes on an aura of legend, and he acts both as though

creating the performance of something which is happening, and of something which has

happened “already.” By the latter means, his life is taking place in a futurity in which it is

read, and in a present in which it is written. The simplest acts and words are invested with

the immediacy of a drama “taking place,” the glow of “great acts having taken place ,”

and, to heighten both drama and aura, the precisions of a prefatory “about to take place,”

which allows for the insertion of the necessary commentaries, directions, and asides. “For

the benefit of the listener, for the pleasure of the reader, for the background material

necessary to the writer,” as El Colonel describes it with relish in a self-penned blurb.

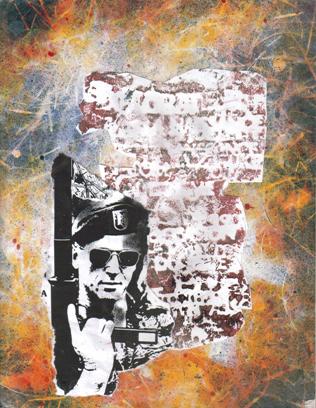

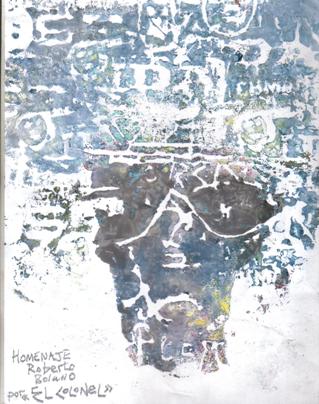

El Colonel smiles. “Implacable face of an idol, obsidian eyes set in burnished copper,”

the handsome adjutant stands before him with the morning’s first batch of dispatches,

files, runner-delivered letters, and neatly folded and crisp “primarily Provincial”

newspapers. The adjutant is one of El Colonel’s pet projects, “a raw recruit before our

very eyes transformed into a perfect specimen of youth tempered with discipline.”

El Colonel smiles. The adjutant’s high cheek bones and broad shoulders “indicate a

physiognomy and physique in harmony with the topography.” “Impassive, inscrutable, O

what rock hewn ages has your being not known,” El Colonel hums as the bright birds

sing.

El Colonel smiles. Snapping to attention, the handing over of the documents being

accomplished, the adjutant speaks in clear, carefully enunciated tones. “Colonel today is

the one appointed for your meeting with El Ojo, at 10.00 hours.”

El Colonel smiles. With a slight broadening of his lips, El Colonel indicates to the

expectant adjutant that he, too, may smile. A smile which El Colonel “knows full well he

is eager to indulge in.” El Ojo is well known to be a great favorite with the men of the

“Heroic Patrol.” His meetings with El Colonel “inspire and arouse curiosity even among

the most stoic.” Sometimes these meetings change nothing more in the daily routine than

this “elevation of interest”; sometimes “they indicate an imminent Action of the Heroes.”

El Colonel smiles, the adjutant smiles. “El Ojo,” El Colonel pronounces with firmness,

and, with a broad gesture indicating that a small table and two large chairs are to be

advanced to the center of the room, adds, “Prepare the strongest Reserve coffee and bring

two pack of unsealed cigarettes.” It is well known that El Ojo will only smoke cigarettes

whose seals are broken before his watchful gaze.

El Colonel smiles. Going to the wide open window he gazes through aviator sunglasses at

the bright birds, the luminosity of the landscape and “reflects on the irony that reflective

glasses shield one’s reflections from observing eyes by their mirrored reflections of a

thwarted inquiry."

|